Like many, I've been astonished and concerned as I observe the mutual hostility that now characterizes our national discourse. President Biden aptly named it "uncivil war." The rhetoric on my social media, disproportionately fed by white male retired naval and marine officers and their circles, is overwhelmingly hostile to our new president and congress and condemns each day's actions as evidence that Democrats are destroying the fabric of our democracy and establishing an authoritarian state. This angst is not something to be dismissed. It is not merely our traditional venting of accumulated toxicity by the losing side in response to a political setback. These folks are voicing alarm about a potent existential threat and, as strong leaders in their circles, are responding with echoes of January 6th. Some even affirm a now-circulating Declaration of Independence from the United States and anticipate eagerly a coming uprising during which patriots will deliver our country from authoritarianism.

All of this is alarming, but I believe it should be somewhat less scary if you've been listening to the Race on the Rocks podcast. If so, you know that this rhetoric and these hostilities are not new to our nation. We are experiencing trauma like we have experienced each time the balance of political power has shifted to leaders whose top priorities include reforming our institutional structures and norms as needed to transition to a multiracial society.

This week's episode describes how Lincoln, the leader of the nascent Republican Party for which those priorities were generative values, experienced a dilemma like ours today. He saw no course he could take to avoid half the nation responding violently to what they experienced as an existential threat to its way of life.

In a future episode - I believe it is #14 - we recall the Southern Manifesto, a defiant proclamation in response to the Supreme Court's desegregation orders accompanied by similar tribulations and fear of an existential threat to a cherished way of life. When we recall our history, today's rhetoric about the destruction of our democracy, the calls to secession, and demagoguery about imminent socialism echo our 1950's soundtrack. We have experienced this trauma before, and, like our forebears, we can figure this out.

I've been trying to understand the existential threat experienced by folks who look like me, talk like me, served our country alongside me, profess faith in the Way of Love like me, and who, like me, strive each day to be the best American citizens they can be. I am trying to make sense of a few observations and invite you to think alongside me as we struggle through this historic moment.

My first observation is that the efficient cause of our trauma is fear. The reason leading to the rhetoric and the clarion calls to battle stations on both sides is the fear that something precious is at stake. Recognizing that fear is the underlying cause is crucial because we know the antidote to fear. Here I make a theological claim that is for me both diagnostic and prescriptive. The Apostle John wrote to Christian communities he led at a time of great ferment and persecution. He reminded them that, "There is no fear in love, but perfect love drives out fear, because fear expects punishment. The person who is afraid has not been made perfect in love" (1 John 4:18). As someone enculturated as a warrior, my reflexive reaction to my neighbor's aggressive posture is to meet his stance with equal and opposite force. Yet, John is undoubtedly right in pointing us to Jesus' emotive response to fear. We disable fear, not with power, but with love.

If you've read The Art of Blessing, you know what I think our Lord prescribes for us. We have to figure out how to offer ourselves to our threatened neighbors in such a way that we channel Christ's adoring efforts to sustain and share his peace with them. There is no cookbook here. It's jazz. Love redirects the neighbor's gaze to the grounds of hope that are obscured from view by fear's distorted lens. Love addresses the fear.

My second observation is that the object of the fear generating our trauma is the loss of freedom. The existential dread is that a cherished way of life may end, but the perceived foundation of that way of life is freedom. "Socialism!", spoken in dread, does not denote the theory of political economy in which the state and the markets each play essential roles in generating the innovative products, social goods, and security we demand. Instead, it denotes a montage of authoritarian regimes whose sins against the people were empowered by their promises of a more just and equitable political economy. At stake is not a mundane preference for laissez-faire policies for Main Street. At stake is freedom itself.

If this is correct, then it seems that two responses to that fear may be fruitful.

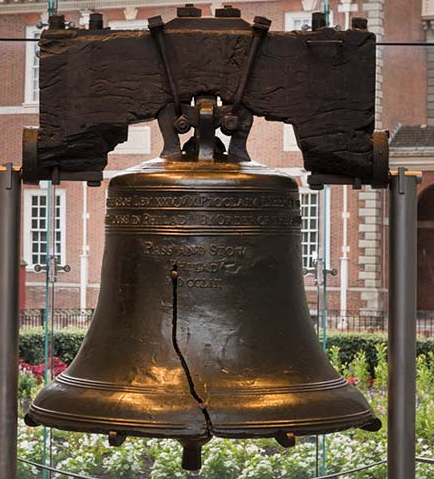

First, we name our common ground. These certainly are among our grounds of hope. We are constituted as a people by a set of common paramount values articulated in our founding documents. We share the priority of securing "the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity." Alongside our commitment to securing these blessings, we also share the co-equal priorities of establishing justice, ensuring domestic tranquility, providing for our common defense, and promoting the general welfare. Our ongoing responsibility as American citizens is to figure out how to establish, insure, provide, and promote these core values while at the same time securing the fruits of liberty. There ought to be no debate about our mutual and objective commitments to these values since we receive them as givens. They are the inheritance we pledge to steward.

Second, we stand firm in defending a theological understanding of freedom against the modern distortion that empties it of its depth.

Briefly, a theological understanding of freedom begins with thanksgiving. God has provided a superabundance, much more than we need to live in friendship with God and each other. All created things, including the institutions we receive, are given by God as means by which we may be sustained and drawn into these covenantal friendships. As John Calvin noted, because of sin, our minds tragically are factories of idols. We habitually use our creativity to ensnare ourselves and others in cherishing things and concepts unworthy of worship. As a result, the institutions we inherit and pass on to our posterity, meant to be blessings, are always an ambiguous mix of the good and the profane. Every generation stewards these blessings. Stewardship of imperfect institutions is the context presupposed by a theological understanding of freedom.

From a Christian perspective, freedom is not a right. Freedom, first and foremost, is a gift. It is a gift in two senses. First, freedom is deliverance - liberation from the idolatrous concepts and evil systems we create that trap us in despair and prevent our flourishing. Second, freedom is a calling - a summons to construct a life that participates in Jesus's reconciling work that draws all people into God's love. That calling is a gift that, when accepted, infuses our lives with the depth of grace.

Freedom is thus liberation so that we might go about our calling to become fully human. But as Jesus teaches through the example of his life, being fully human is to be the image of God, the pattern of which is self-offering so that others may flourish. He freed us to practice unimpeded the art of blessing, thereby tasting the fullness of peace and joy we desire.

Freedom, in other words, is not liberation from all things and all people who may make a claim upon us or prescribe the boundaries of acceptable behavior. On the contrary, freedom presupposes communities and institutions' roles in equipping us for how we go about our calling to construct a Jesus-centered life. Our communities, institutions, and nation are an ambiguous mix of the profane and the good. But it is to the task of healing these, and not the task of fleeing these, that freedom calls us as we join Jesus in his work of reconciling the world.

The modern concept of freedom we see at play in our trauma is a distortion. It is not true freedom but an idol. It sees freedom as a right rather than a gift. And, perversely, it turns the idea of freedom upside down by stripping it of any notion of calling except the call to defend and propagate itself. In that sense, it is a virus infecting our people.

The modern concept of freedom is not a liberation from the idols and evil creations that ensnare us, but independence from anything, any group, and any person that can make an unconditional claim on us. Nor is modern freedom a calling to construct a life that cooperates with God's reconciling, justice-creating work. Modern freedom has forgotten that no man is an island.

Modern freedom names all possible actions as theoretically permissible, subject only to our private judgment. To the extent we constrain our behavior because institutions like the state, school, work, or church demand it, our constraint arises not from a sense of dutiful submission to that institution's norms but from our consent, which we may withdraw. Modern freedom sees our lives primarily as self-constructed and minimizes its view of duties to institutions that created the opportunities and foundations with which we construct our lives. Consequently, modern freedom sees our property as intrinsically private, and claims by institutions upon our property - in the forms of taxes or public policies that constrain our free use - as threats to our freedom. [1]

Finally, modern freedom sees the priority of individual will as the only absolute. Truth is not something given or received but offered as a proposal for private adjudication. For this reason, truth-seeking is not a communal task, but, having no absolute foundation, a war of wills. Truth is the invention of the reigning king of the hill. Modern freedom thus begets nihilism.

My observation is that this distorted view of freedom generates the sense of existential fear on display in our real and virtual public squares across our land. It causes a feeling of persecution, the clinging to unwarranted claims, and the calls to arms. Given that view of freedom, these behaviors may be seen as rational, even if mistaken. Democrat public policies will indeed assert more significant claims by the nation upon the individual's turf to which modern freedom clings. Those claims will likely take the forms of taxes, limitations on behavior in support of public health, paying higher wages to employees, limiting our ability to discriminate on Main Street in ways honored in the past, and demanding significant financial sacrifices in the present to forestall a contended climatological future. Setting aside the merits of proposed policies, they collectively may infringe significantly on the private space that becomes an idol when seen through the lens of modern freedom. For these reasons, I view the ideology of modern freedom as the key obstacle to ending our uncivil war.

Moreover, I think this distorted view of freedom is the critical barrier to our transition to a multiracial society that is fair and provides real and exact justice for all of our citizens. For that transition necessarily requires a subjection of and a sacrifice by the empowered for the good of all. Such an institutional demand can only be viewed as theft if the spaces we occupy are ours by right. The only way I see to avoid calamitous trauma en route that vision is to restore in all Americans the love of true freedom that liberates us expressly for the vocation of blessing our neighbor with the jazz that riffs unceasingly on the chords of peace.

[1] For a detailed discussion of classical liberalism's freedom - what I've called modern freedom - see Douglas Campbell, Pauline Dogmatics: The Triumph of God’s Love (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2020), ch 9.