Not long after my wife and I were blessed with our love, she dubbed me "the officer-in-charge-of-hope." She said, "You have enough hope for both of us." She spoke the truth. I joyfully confess that I've been blessed abundantly with the gift of hope.

In his account of virtue, St. Thomas Aquinas names the virtue of hope as the Holy Spirit's gift. 'Virtue' denotes a habit so thick that it becomes one of the sinews of our character that sustain us as we walk along the Way of Love. Though we can progress on our own in developing the cardinal virtues of justice, prudence, fortitude, and temperance, we cannot embody them in their fullness without the Spirit-given virtues of faith, hope, and love. Indeed, the twin gifts of faith and hope work together to generate the thick habit of love. True love requires more than a box of chocolates.

We can't reason our way to either faith or hope. In Aquinas' medieval lexicon, faith and hope begin with God's movement of our will with grace and then our will's movement of our intellect. But the nature of our intellect's action is not an acceptance of creeds or doctrinal propositions about God, but rather an acceptance of God's acceptance of us. For example, the intellect affirms that God's nature is to deliver us from our prodigal ways and that, if we return home, we ultimately will rest forever in the loving embrace of a Father filled with pathos given our plight (Luke 15:11-32). So there is a decision about what is true and the source of truth, and there is hope in things unseen.

But notice that hope has two important elements.

First, hope necessarily has an object. For me, hope's object is the world the Bible signifies in its portrait of the New Jerusalem, that fulfillment of time when all things are created new and "Death will be no more. There will be no mourning, crying, or pain anymore…" (Rev 21:4-5). In the New Jerusalem, God's creative justice reigns eternally. That’s the object of my hope.

Second, hope has a cause that makes our object possible. Hope, by definition, excludes that which we believe is impossible. To hope in something necessarily means we believe in its possibility. Hope also includes the expectation that something will happen for which there is a cause beyond ourselves; hope trusts that the thing hoped for is possible only with some assistance. I address hope's cause as "God."

To some folks, hope seems a fantasy, an unwarranted optimism that is blind to the facts of our reality. This is especially true when all we see is darkness, and all that we feel is emptiness. Yet hope corrects our vision, helping us to see that the victory of darkness is but an illusion caused by our narrow field of vision. To borrow a phrase from Samuel Wells, hope redirects our eyes to “the grain of the universe, that is along the contours of cross and resurrection, remembering God's surprises and anticipating God's transforming future.” Hope confronts courageously the tension between today’s reality and the New Jerusalem, and propels us along the Way of Love.

I've been thinking about the virtue of hope lately because many have named for me a suffocating darkness they feel as they experience the agony of separation from loved ones due to the pandemic and as they lose cherished relationships to the arrows of our savage civil zealotry.

I've been crushed by the weight of nothingness, too. An Annapolis classmate boasted of his presence the day they stormed the Capitol. A platoon of conspiracy theorists swamped my social media, spewing venom and peddling nonsense in their quest to trivialize the virus and discourage folks from communal actions to combat it. A lawyer argued we have no duty to protect our neighbor from the infection that we ourselves carry. And, most disturbing for me, a barrage of posts loudly proclaimed friends' unwillingness to tackle the unfinished work in our American arc toward justice. The darkness enveloped me, yet hope shines in the darkness, "and the darkness doesn't extinguish the light" (Jn 1:5).

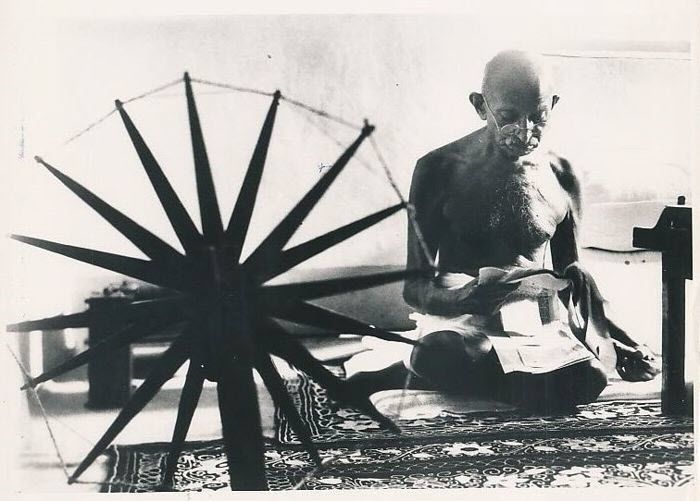

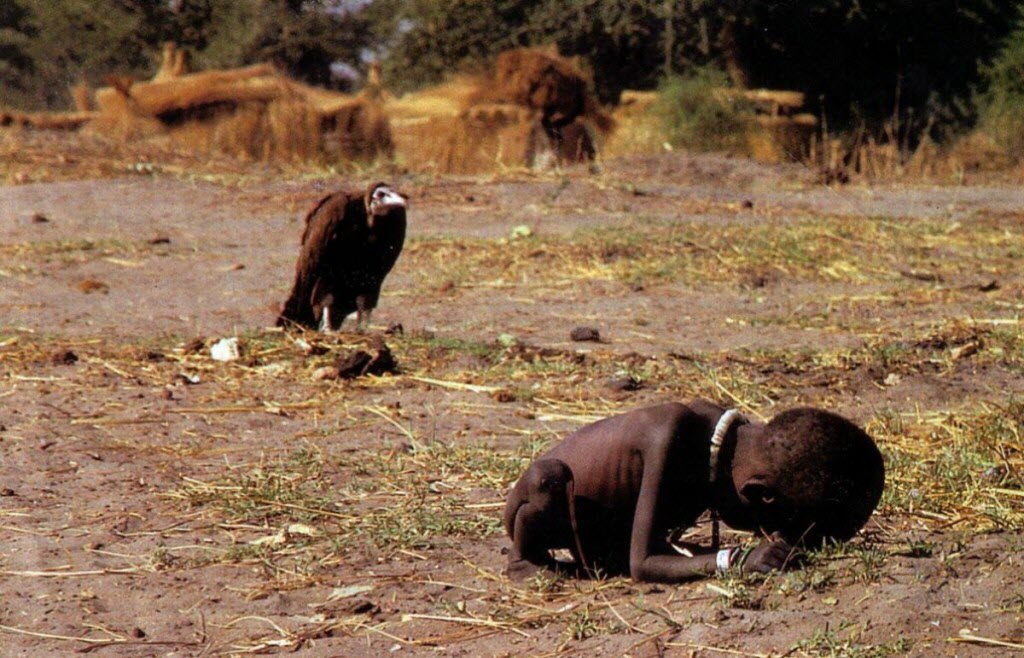

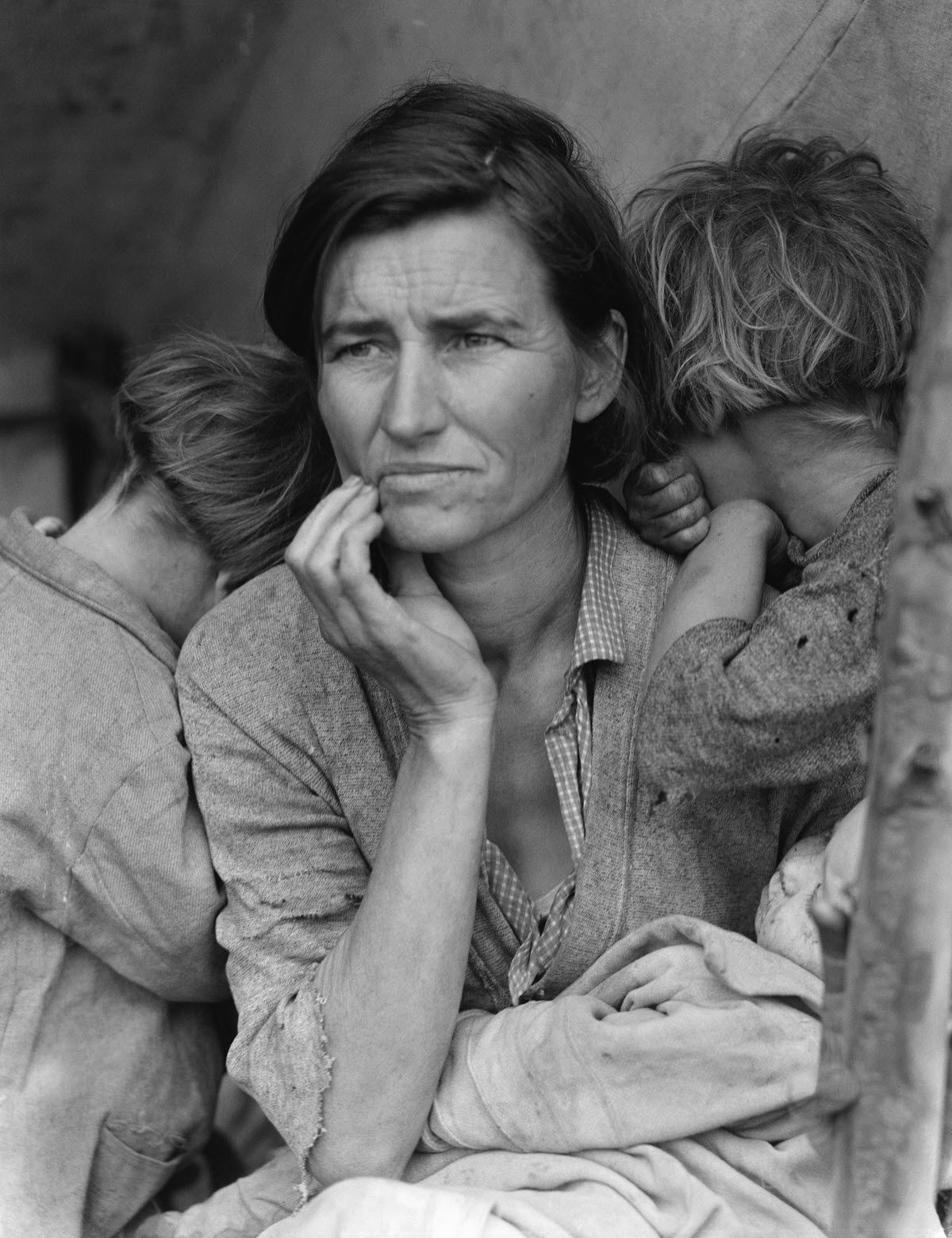

Remembering the light led a friend and me to remember how the prophets' poetry steeled the Jews in times beset by darkness. Our longing for such prophetic comfort led us further into a discussion of what constitutes prophetic art.

The arts have always had the essential function of grasping and criticizing the world as we have shaped it. Artists help our hearts see our forms of separation from God and each other and afflict us so that we are driven to close that distance.

Christian art emphasizes both the infinite distance and intimacy between God and creation. It often emphasizes our human limits, our subjection to death, but above all, our self-alienation and our vulnerability to forces of self-destruction. But it also sounds the good news of God-with-us. Great Christian art brings into our present moment either the noble beauty of God's splendorous grace or the gut-wrenching ugliness of our rejection of that grace. It asks the questions of life to which God is the answer.

Do you have a camera, a paintbrush, or a pen? I am praying for God to raise up prophetic artists in our midst who can speak God's Word of comfort to us as we endure this Alice-in-Wonderland chapter of our American story.

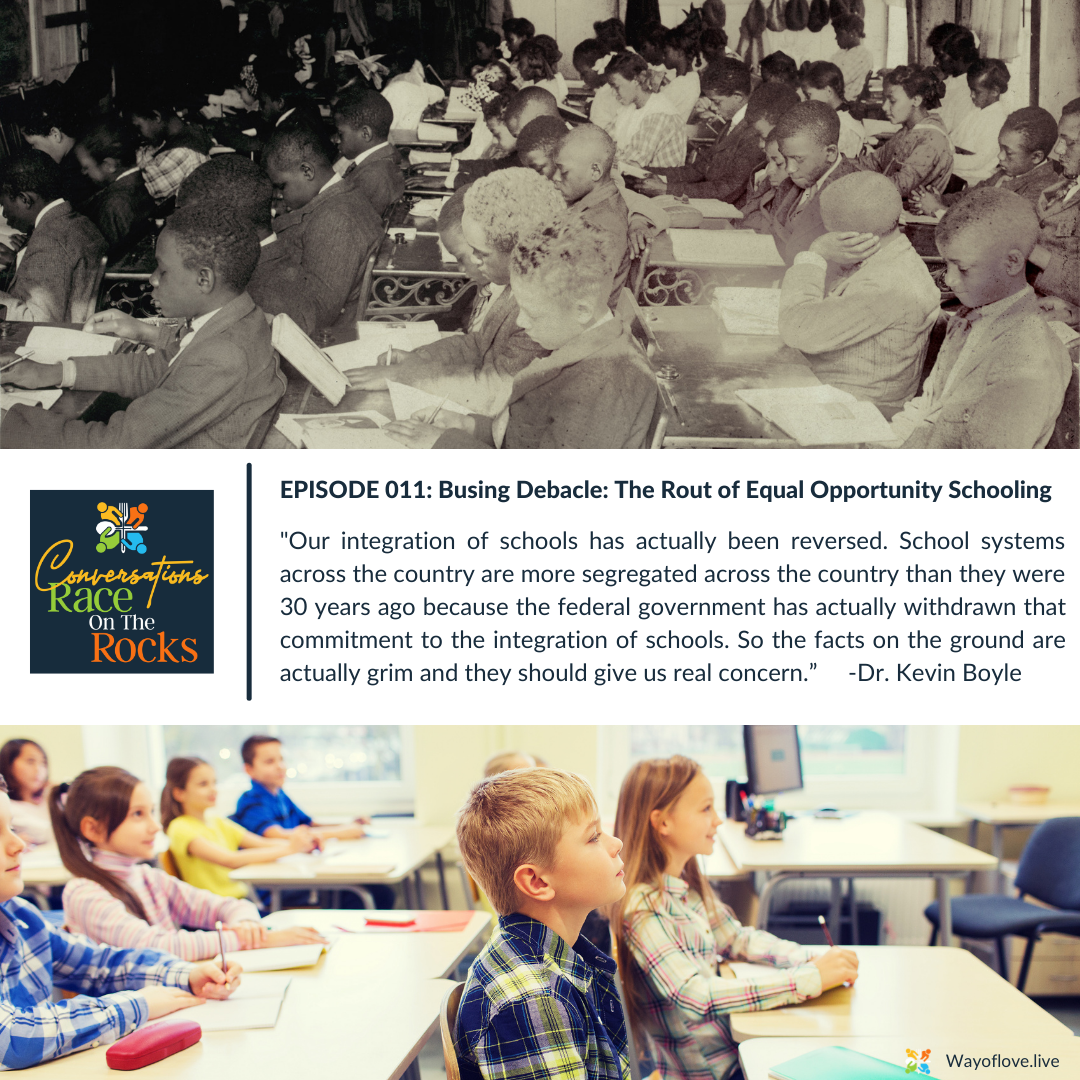

The Busing Debacle: The Rout of Equal Opportunity Schooling

When I was a kid in Baton Rouge, Judge John Parker's name was of household fame. I didn't understand much about consent decrees or forced busing, but I knew Judge Parker was presented as the villain in the news each night. I didn't understand the backstory, context, or the other side of the story that led to my father's recurring rants about Baton Rouge school buses circumnavigating the globe each day. I just knew that desegregation meant that 35% of the faculty at my white public school had to be Black, and not much else changed. In my adolescent bubble, I had no idea that my school was a tiny part of a massive battle in which my forebears defied the authority of the Supreme Court of the United States. Like them, I could not foresee how tragically that defiance would impact us in 2021.

In this week's episode of Conversations: Race on the Rocks, we pick up where we left off in our discussion of the right to choose one's habitat as a segue into our discussion on education and schools’ desegregation. What progress did we make in the 60s and 70s, and how has that progress impacted us today? Dr. Kevin Boyle connects the housing regulations we discussed in the last episode to the problems the country faced in schools during that time. Although Dr. Boyle shares that our progress continues to be painfully slow, he gives us grounds for hope as we continue to try to move forward in understanding the racial tensions of the past and present.

Listen now on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher and more!

"The Real American Dilemma"

I noted above the darkness that enveloped me as I listened to the social media barrage with which friends rationalized their commitment to reverse gains made in our quest for free and equal and exact justice for all. The way forward looks perilous in the short term. I think my friends are repeating both the mistakes and the rhetoric of the 50s and 60s. In this essay, I point to a different trailhead. Now is the time to press forward to the summit, not descend to our base in a cloud of cynicism.

Called to Disrupt

In this week's message, Jesus calls his first disciples and turns their world upside down. He calls us to be "fishers of humans," which, when we understand his scriptural allusions, destroys our carefully protected dichotomy between the personal and the political. When we follow Jesus, the personal and the political become one. Rather than a band of Zealots, Jesus recruits a band of artisans who fish for humans by sharing their bread.

Lagniappe Love

I spoke above about my prayer for a bounty of prophetic art that speaks to our time. A few years ago, Lonnie Lynn, Jr., whose stage name is "Common," released this wonderful example of what I mean. It's the theme for the documentary 13th, and titled Letter to the Free. Turn up the bass, and enjoy! May it move your heart as it does mine!