Not long before I left Baton Rouge for grad school, I made my father's blood boil. Provoking Dad was my unfortunate forte, but that night's fury bewildered even me.

We dined late at the Country Club of Louisiana. As we awaited the food, I enthusiastically shared stories about FDR, Churchill, and their leadership during WWII. I tend to digest libraries when I focus on a subject, and that night I was that 40-something kid, regurgitating to my parents all that fascinated me about my latest passion. Speaking admiringly about FDR's adroit leadership, I listed several widely known obstacles he overcame. One of those was Charles Lindbergh's respect for and aggressive defense of the Nazi regime in Germany. That's when Dad blew a gasket.

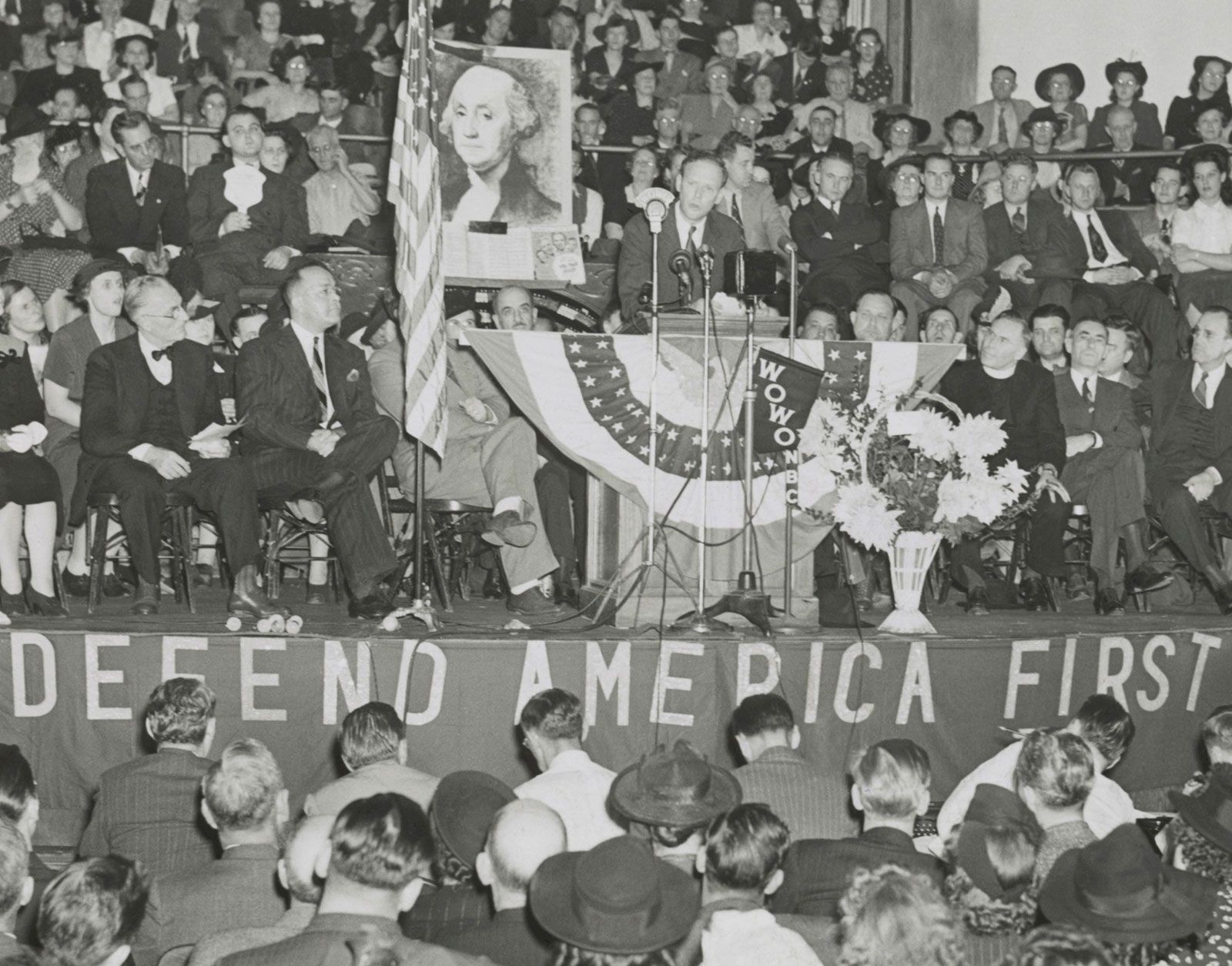

In retrospect, I made two miscalculations in my matter-of-fact naming of Lindbergh's notorious role as the spokesman for the anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi America First movement. First, Dad relied on his keen intuition. He navigated daily headlines, interpreting the present in terms of his personal experience and contemporaneous wisdom from those he trusted; he didn't know or invest time studying our past. Second, like Lindbergh, Dad was a German-American reared in the Midwest. My father grew up in St. Louis, and he was captivated by Lindbergh's flight aboard the Spirit of St. Louis. Lindbergh was his boyhood hero.

When I alluded casually to Lindbergh's infamy, which I assumed was common knowledge, Dad exploded. I remember the tinkle of the glass when he pounded the table in resistance to my speaking critically of his hero. He was instantly indignant. "No! You will not disrespect Charles Lindbergh. He's a great American hero! How dare you spread lies about him!"

For Dad, Lindbergh was the great American hero who defied the world's imagination by flying from St. Louis to Paris. For me, he was the celebrity who proudly wore the Service Cross of the German Eagle that Nazi Field Marshall Hermann Goering presented him, who planned to immigrate to Berlin but instead became a tool of the German propaganda machine here in the U.S. My father knew only the famous flight, but I knew his unsavory history, such as his Reader's Digest essay in which he told whites "racial strength is vital," and "that our civilization depends on a Western wall of race and arms which can hold back... the infiltration of inferior blood." I knew of his shameful America First speech in Des Moines when he said:

Instead of agitating for war, Jews in this country should be opposing it in every way, for they will be the first to feel its consequences. Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government.

Dad would hear none of it. In a way I could not fathom, he preferred to preserve the myth of an infallible hero than to learn from the reality of a man in whom heroic and anti-heroic tendencies competed.

I recalled that painful moment with Dad this week as I reflected on our national discourse about monuments and memorials. The San Francisco school board recently decided that they would no longer name schools after George Washington, Abe Lincoln, and other national heroes the board perceives to be on the wrong side of history. Washington and Lincoln were among forty-four leaders whom the board felt "engaged in the subjugation and enslavement of human beings … oppressed women ... led to genocide; or … diminished the opportunities of those amongst us to the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

That provoked indignations similar to my father's from Americans across the political spectrum. It's yet another nonsensical attack on something sacred, something to be preserved at all costs, and evidence of the moral degeneracy of their political opponents. In their outrage, they won't examine the realities concerning those leaders that cause an increasing number of Americans to reevaluate their current celebration as heroes.

I count myself among another group who are open to the conversation but who meet with furrowed brow the suggestion that Washington and Lincoln do not have an assured place among the crème de la crème of American leaders.

A Black social media interlocutor explained:

… remember one key fact, none of them ever experienced the sting of whips, had their limbs chopped off, were raped in front of their families, nor did they feel ropes tighten around their necks. Those were monstrous acts then and would be today. In fact, many of those acts, with the exception of slavery, albeit the system of peonage taking its place, persisted until the 1960s. So, please understand the PTSD those acts caused in the victims and their families for generations. I guarantee you if the situation was reversed, you'd have a much different perspective regarding the history of our country…. I'm saying to you that some black and brown people don't care about the nobler aspects of the historical figures you describe. Those aspects don't redeem them in their eyes. [Emphasis added]

So, on one side, we have folks who can't handle fresh criticism of heroes they were taught to cherish. On the other side, we have folks who insist we knock down monuments and rename ships, bases, buildings, and schools that commemorate those historical figures because their alleged failure to represent values we need to emphasize strongly in our time. In the midst of these are those who feel so bruised from generations of abuse that commemoration of certain figures triggers their trauma, ripping them out of the present moment as they re-experience the whips, the chains, the false arrests, the knees on throats those figures failed to stop.

What are we to do?

My first thought is that we need to ratchet back the rhetoric and return to a civil discourse that presumes that our neighbors are neither idiots nor ill-willed. Let us never be a nation where it is unsafe to have a conversation about the naming of things.

Second, we need to call all citizens to make rational distinctions and refuse to feel imperiled in the encounter with truth-telling. The truth is where justice and mercy meet. Love of neighbor endures only at that intersection.

George Washington and Abe Lincoln don't need us to defend them. Their stories already do. Knowing history had its eyes on them, they already spoke through the tapestry of their lives. Our myths remember well their glory. Historical reconstruction that names their failures helps us color their humanity so that the moral heights they nonetheless ascended seem possible for us, too. They also warn us of the ever-present danger of grounding our republic on a cult of personality rather than constitutional order because, for even the greatest among us, "sin is lurking at the door" (Genesis 4:7).

We need not protect Washington or Lincoln from charges that they embraced rather than rejected a white supremacist world when they lived. A white supremacist is a person who supports policies that create or sustain communities ruled by a white-dominated hierarchy. It's beyond question that Washington and the vast majority of our Founding Fathers held that view, though they were considerably more complicated than that view reveals. Lincoln had an arc of discernment: he began supporting the Liberian colonization idea and took a long time before he could imagine how the law could permit emancipation of the enslaved and did not embrace the idea of enfranchisement until just before he died. We can afford to name these truths without feeling their greatness is diminished. They themselves owned the discrepancy between the American ideals they imagined and the reality they lived. We can, too.

We must make key distinctions. Naming truthfully that discrepancy is different from concluding we should remove them from their place of honor.

A commemoration is an act of rational reconstruction. Having historically reconstructed the stories we tell about them - liberating ourselves from unhelpful and untruthful myths - we choose to invite some luminaries to our present conversation about how best to embody the constitutional ideals we now steward. Whom do we invite? Which of our great leaders warrant a seat at today's table because the tapestries they wove on their watch can speak wisdom into our current situation? Which forebears' stories can help us to recognize and move boldly towards "whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is pleasing, whatever is commendable" (Phil 4:8)?

Every generation stewards our national dream in a unique context. That's why it is appropriate for every generation to reflect on whether our monuments, ships, schools, and buildings speak the stories we need to recall in our current moment. We ought never to be afraid to have that conversation.

Which forebears can speak wisdom into our national discourse today? How do we discern?

Some folks want to exclude from our national dialog any forebear who held positions that today's rational person of goodwill would find unacceptable. No matter their achievements, forebears whose story includes views we reject today are irredeemable, by definition. Such forebears, the argument goes, should be purged from our civil pantheon. We should tear down their monuments and re-brand our memorials.

I argue that this approach to discernment is uncharitable and ill-thought. God forbid we ourselves would be held to such a standard! Wisdom should lead us to determine that they were or were not justified in holding particular views based on what was imaginable in their time, though their views or actions are unacceptable in our time. We can continue to converse with the Apostles, even though their models of the cosmos are unacceptable to our Einstein-informed minds. We can continue to converse with Einstein, even though his view of a non-expanding universe is unacceptable in our time. Some luminaries were justified in holding views we reject today, and some were not. We can discern the difference. So we can distinguish easily between Abe Lincoln and John Calhoun, Mahatma Gandhi and Woodrow Wilson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X because they were not morally equivalent in the views they held at the same time. Applying today's standard as a blunt instrument to our forebears retrospectively is uncharitable and imprudent.

We need not fear the renaming, rebranding, and removal of monuments. That's a healthy way communities let go of stories that are no longer helpful and rediscover stories that are. We can discern those stories most edifying to elevate as we face today's challenges through a commitment to truthful storytelling. We can celebrate our greatest leaders' achievements while simultaneously remembering how their failures of imagination and sins instruct us in humility today. People of goodwill can hold these distinctions at one time with integrity.