This week, my wife had to lift me up. I was down because I have been feeling the weight of just how hard it will be for us Americans to become what we say we are. Like substance abusers, we have no hope of becoming who we imagine ourselves to be until we are honest about our gaps.

We began as a thought experiment. In the comfort of triangle trade wealth stacked by Middle Passage cargo, our founders asked, "What if we took seriously the Enlightenment fiction that all men are created equal?" The question begat a dream. We've been working out the answer ever since, proudly claiming the dream's fulfillment and moral power and canceling consciences enflamed by the breaths of black and brown discrepancies in our tale.

The substance abuse metaphor speaks our truth. Our differences matter. There is no unity that eclipses our diversity. Yet when it comes to today's struggle to "achieve our country," there is only one category that matters. There is neither Hispanic nor non-Hispanic white nor Asian nor Black nor American Indian. There is neither Republican, Democrat, or Independent. While real and important, none of these identities are ultimate. To borrow a phrase from Pauline scholar Douglas Campbell, the only relevant category is whether or not we are striving to rehabilitate a worldview sickened by hierarchies of human value.

I sought my wife's encouragement this week because my social media feeds are filled with the rhetoric we whites have used for decades to sedate our consciences when faced with evidence that our American Dream is not yet fulfilled. Friends confuse patriotism with chauvinism, not recognizing that authentic patriotism is that which truthfully names our discrepancies and calls each generation back to the task of answering the question that begat our American Dream.

Yesterday, as Congress conversed about the slaughter of eight Asian women in Atlanta, California Congressman Tom McClintock gave voice to the perennial rhetoric that resists demands that we live our dream: "To attack our society as systematically racist, a society that has produced the freest, most prosperous, harmonious multiracial society in human history, well, that's an insult." In our citadel of democracy, the congressman voiced the lie we tell ourselves: The dream is fulfilled, and the City on the Hill is not merely our vision but our fait accompli. And anyone who points to the discrepancies in that story is slandering the hard-working, God-fearing citizens of this land.

What is it that we fear? What do we whites feel is at stake when confronted with evidence that we are not yet done creating that equal opportunity nation that was an acknowledged fiction at our founding? How is our identity threatened by proof that we have more work to do? Or is the fear really about what that work entails? Are we terrified by the recognition that the only way we Americans can attain enduring moral power is through the sacrificial self-offering of white power?

Today we recorded the 24th episode of the podcast we call Conversations: Race on the Rocks. We talked about our land's landscape and how we cling to patches of habitat as we pursue our constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property. Highways, hurricanes, flooding, and brownfields contaminated by decades of accumulated toxic waste: we named structural risks and limits in habitat choices disproportionately borne by non-whites throughout our country. We named enduring concrete structures - literally the kind made of a mix of stone, sand, cement, and water - that were built to exclude non-whites from common pleasures or exclude whites from common risks. Like evil sacraments, these concrete structures both enact and signify something beyond themselves - the hierarchy of human values that blocks our way to the American Dream.

If you've listened to the podcast through episode 11, I suspect that you, like me, have joined the ranks of those actively seeking liberation from that worldview based on a hierarchy of human value. If you've not yet listened to it, let me challenge you to take that risk. One listener recently wrote to name the episodes as "refreshing." The journey is not a white guilt trip; it's learning the parts of our story that complicate claims that we've achieved what our founders dreamed. Once we get a fix on our position, we can plot a course that fulfills that dream.

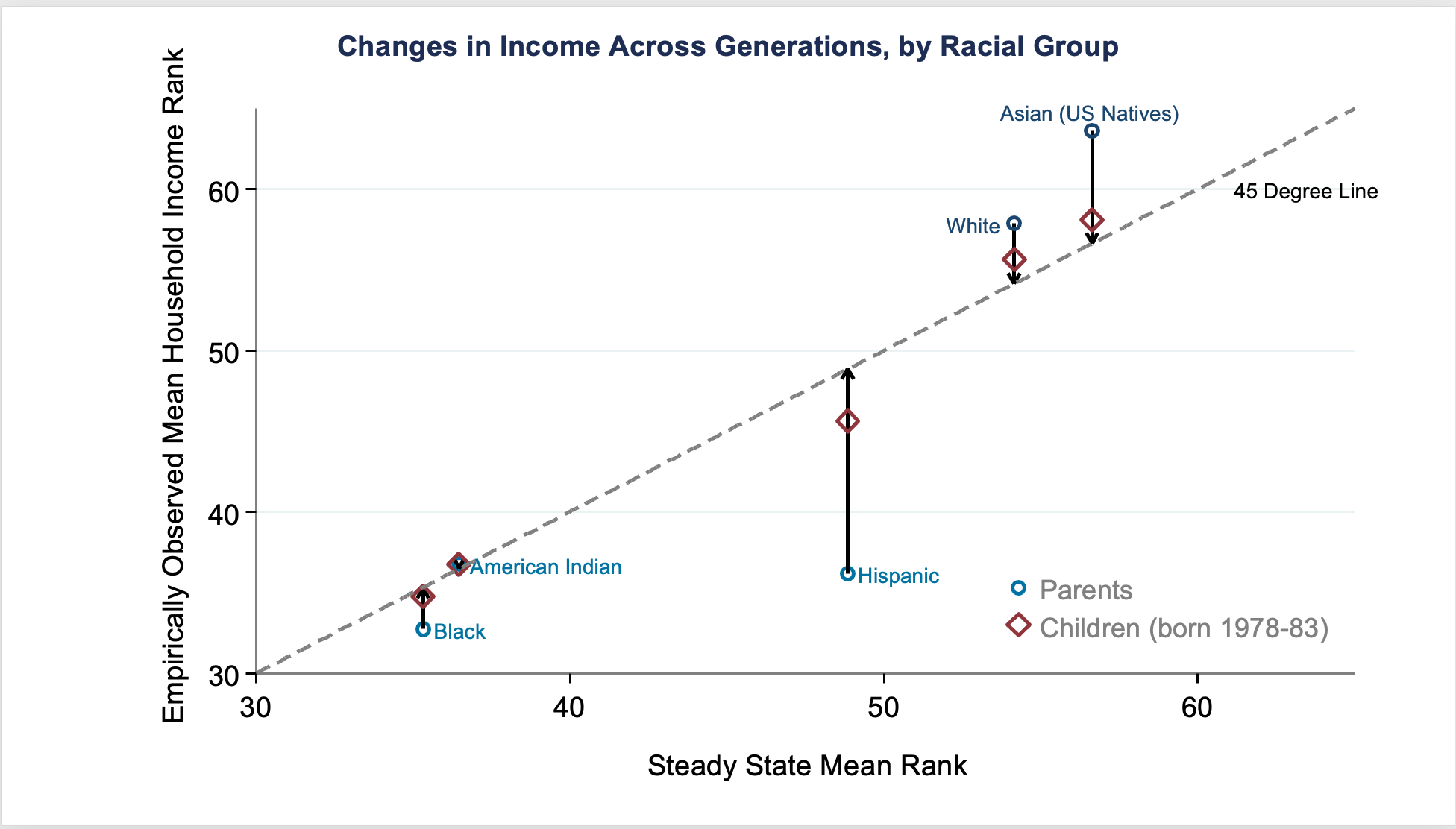

But if you are among those committed to denying the reality of structural discrepancies that thwart our dream, then I urge you to digest this data from Harvard professor Raj Chetty. Chetty and his team achieved something remarkable. They tracked 20 million parent and child groups longitudinally using census and IRS data so that they could measure the impact of various factors on their flourishing. They focused on the mobility of children in terms of their climb up the income ladder as adults. Their findings are fascinating and filled with insights about the way forward. The bottom line is that they demonstrate that we have not yet achieved our goal of equal opportunity in terms of the reasonable probability of people lifting themselves out of poverty. That probability varies along racial and gender lines.

For example, white children born to parents in the bottom household income quintile are 424% more likely than blacks to rise to the top quintile. Moreover, the study gives us the data to reject the contention that this black-white gap has to do with innate ability differences between blacks and whites. It demonstrates that we can't blame the gap on differences in family characteristics. The study notes, "Parental marriage rates, education, wealth — and differences in ability explain very little of the black-white gap."

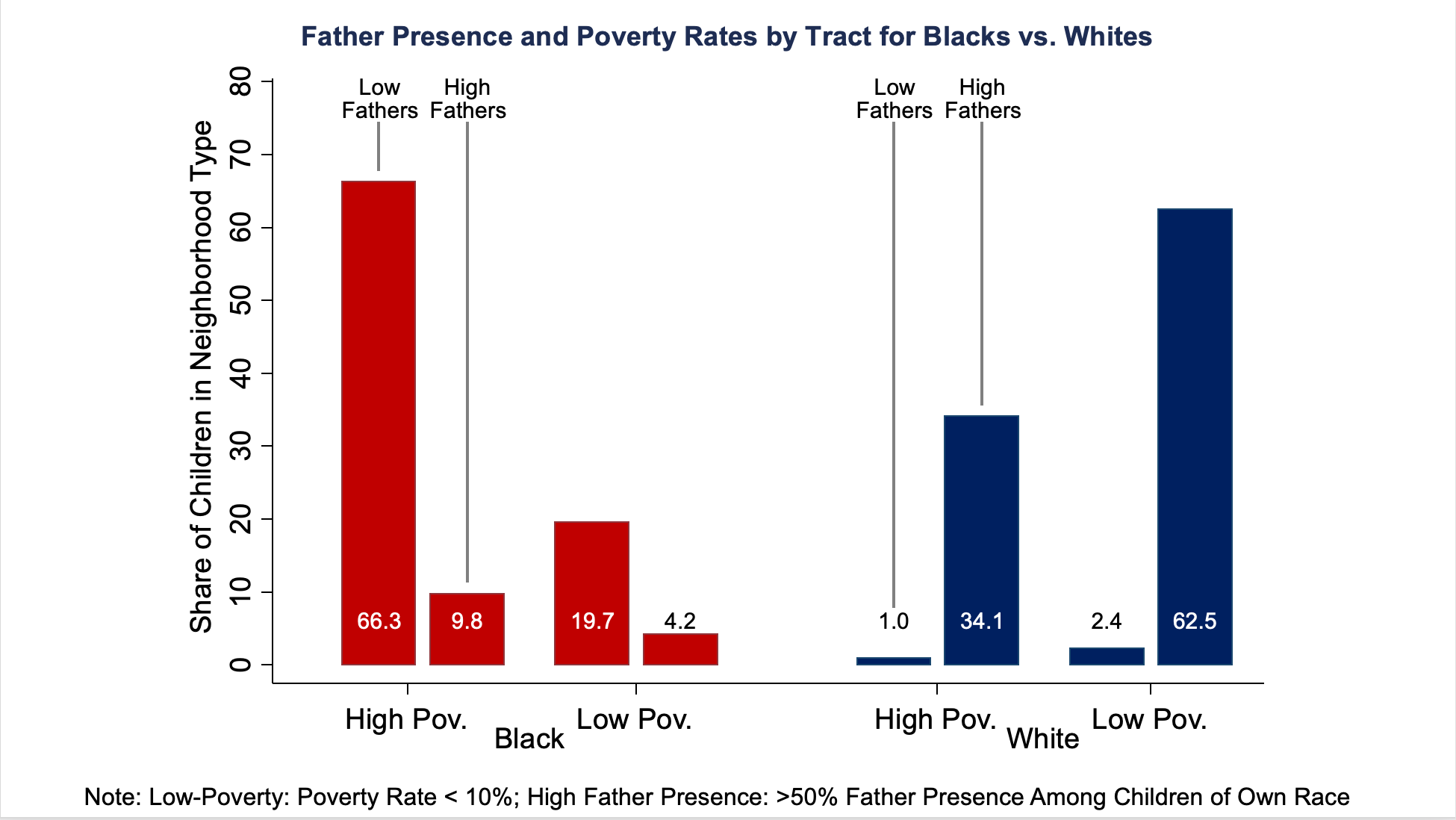

I found the key insight in the weeds of their Powerpoint presentation. Three factors drive the black-white gap in terms of upward mobility: "Black boys do well in neighborhoods with good resources (low poverty rates) and good race-specific factors (high father presence, less racial bias)." Importantly, it is the presence of black fathers within the neighborhood and not within the home that is statistically significant because these provide role models and support that make a difference. The problem is that "fewer than 5 percent of black children currently grow up in areas with a poverty rate below 10 percent and more than half of black fathers present. In contrast, 63 percent of white children grow up in areas with analogous conditions."

'Structural racism' names this difference in the opportunity to flourish: Because of our history, today's American children inherit different probabilities of upward mobility based on the block on which they grow up. We've not yet become the land of equal opportunity. That's the fact behind the phrase Congressman McClintock finds "insulting."

Since before our founder's thought experiment, we whites have tipped the scales in our favor, and our tipping over time etched the terrain indelibly with the signature of our sin. The living waters flow disproportionately in our land to white gardens. Our founders acknowledged the discrepancy and nonetheless dared to bequeath us their unfinished dream, trusting we would reconcile on our watch what they could not reconcile on theirs. Our forebears heretofore could not do so, but with their freedom-riding blood, they've turned over such an abundant and promising land that we have no excuses left.

The real American dilemma is whether to be drowned in our history or to use it, to persist in myths or to set a new course toward the dream. Now is our time. We have nothing left to fear. We can relinquish the lie and finish the honest work of becoming a nation where all men and women experience equal and exact opportunity and justice. That's the true path to making America as great as our dreams.

If we - and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others - do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. - James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time