Congress and state legislatures are focused on reforming how we vote. There is sure to be a battle over proposed reforms that likely will include adjudication by the Supreme Court.

Today’s news is filled with stories of the many bills filed in battleground states that their authors claim will restore our confidence in our voting systems. Most of these expand voter ID requirements, make absentee voting more difficult, restrict polling times, make voter registration more challenging, and restrict voting by mail.

Similarly, the House has passed HR 1, a bill that sets national voting standards to simplify the process by which we exercise this fundamental right. The bill creates uniform standards for absentee and in-person voting, replaces the process by which congressional districts are gerrymandered with independent, bipartisan commissions, requires the restoration of voting rights to felons who’ve fulfilled their sentence, and requires that states accept an affidavit in place of a voter ID if a person is unable to provide one. HR 1 is unlikely to pass the Senate, so I won’t try here to consider its wisdom.

Your own view of these developments may or may not cohere with the motivations of the GOP and Democrats, with the former emphasizing election security and the latter emphasizing maximal election participation. My own view is that there can be no dichotomy here. We citizens should require both election security and maximization of voter participation by all verified citizens.

My take begins with the paradox of democratic republics: to be maximally inclusive of all citizens, we must be rigorously exclusive. To optimize the welfare of all citizens, we must clarify who is and who is not a citizen. Where power is invested in a dictator or oligarchy, rigor in clarifying citizenship of those outside those circles is less essential. “We the People” necessarily denotes a particular sub-set of those present within our boundaries at any snapshot in time. Accurate and complete registration of our full citizenship is crucial to our republic—verification of voter eligibility matters.

That’s why I see efforts to ensure that only verified citizens vote as reasonable. Indeed, that was the conclusion of the 2005 Building Confidence in U.S. Elections Report by the bipartisan commission led by Jimmy Carter and James Baker. The Real ID their report envisioned - a means by which the states verify our citizenship in uniform ways - is now the law of the land. We’ve not yet passed national legislation to leverage that Real ID for voting as the Commission recommended, though we now use it for commercial travel and other purposes. Like the Commission, I think mandating Real ID use to verify eligibility to vote in a way comparable to their prescription is a sensible approach. The commission prescribed that “voters who do not have their valid photo ID could vote, but their ballot would only count if they returned to the appropriate election office within 48 hours with a valid photo ID.”

My concern with laws making it more difficult to vote is the extent to which they make more likely the unjust denial of historically marginalized groups’ right to vote. The more local the adjudication of this right, the greater my concern. That is, if the law enables folks at the precinct or county level to determine without appeal whether presented ID suffices, then the prospect for voter disenfranchisement is too great to risk.

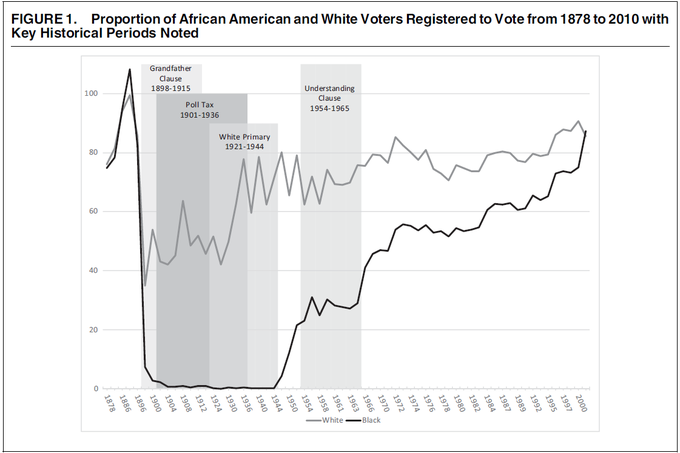

This Cambridge study of Louisiana voting records shows why. The study demonstrates the impact of Louisiana’s law that enabled poll workers to determine voter eligibility based on the state’s Understanding Clause. Citizens had to demonstrate sufficient understanding of the U.S. Constitution to a local official to prove eligibility to vote. Unaccountable local officials thereby disenfranchised non-whites via their subjective decisions that disproportionately denied non-whites the right to vote. To the extent Voter ID laws return citizens to a similar power dynamic in which local officials can deny their right to vote without immediate appeal to state-appointed ombudsmen, the probability of voter suppression is too great. We can press on until we agree on a more just system.

As we participate in the discourse about state and federal reforms of our voting franchise, I urge you to do a close reading of the Carter-Baker Commission Report and challenge lawmakers to embrace all of its recommendations and not just those that provide political leverage for their party. We’d move toward a system that ensures both electoral security and maximal participation by all citizens if the principles established by the Carter-Baker Commission become the law of the land.