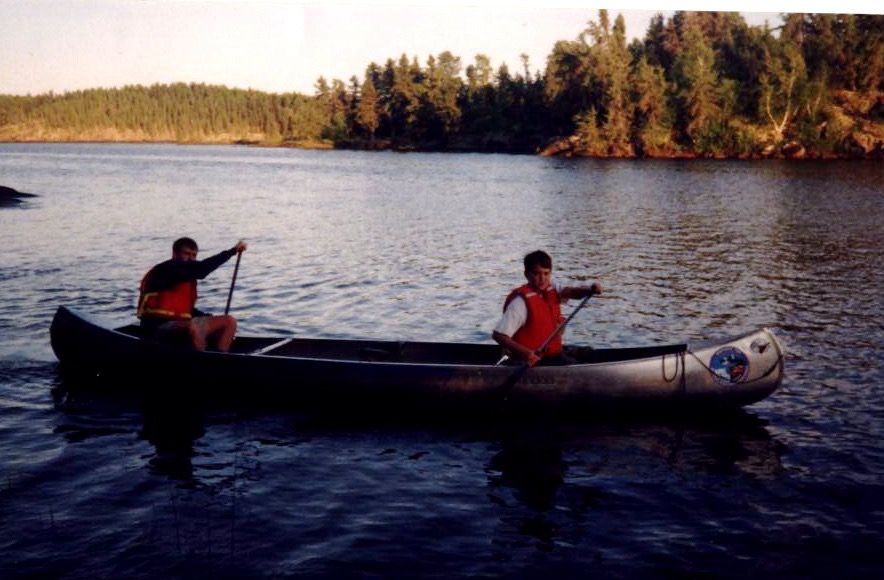

Long ago my brother and I led a contingent of Boy Scouts, including two of our sons, on a canoe expedition deep into the rugged and remote wilderness north of Bissett, Manitoba. It was a journey of transformation that I will never forget.

My son, Andrew, was only 13. He had not yet become the lean, muscular athlete who would stun us by seizing second place in the two-mile race at the state track & field championships. That made the trek extra challenging for him, for we carried all the food and gear we needed for our group to survive ten days in the wilderness. He quickly mastered paddling through rapids, but he struggled during the daunting daily portages in which we lifted the canoes to our shoulders and heavy packs to our backs, and trekked up and over long trails linking the beautiful Canadian lakes. Portages are grueling work for adult men. They were hellish impossibilities for almost-men like my son.

Watching the older Scouts, he tried. But the load was too heavy. The trail was too treacherous. The slopes were too steep. He failed. Repeatedly. At one point, he surrendered and wept those dry tears we weep when we know we can’t possibly carry on another step. But about midway through the trek, something happened. Before anyone could intervene, he lifted his canoe to his shoulders. Another Scout quickly moved to help, but he grunted, “No, I got it.” That day, my boy achieved his first solo portage. That day, he conquered. Transformation.

I don’t remember our destination on that wilderness journey. All I remember are those moments of transformation amid the exquisite beauty of the wilderness. Eagles soared and so did our almost-men sons. Perhaps those moments, and not quickly forgotten geographic coordinates, were always our destination.

I haven’t thought of that expedition in many years, but today, as I contemplate inviting you to join me on a different kind of wilderness journey, those wonderful moments of transformation come to mind. For the journey I set before you has no final geographic coordinates I can name, no universal compass bearings I can prescribe. As on that trek long ago, those moments of transformation amidst beauty are themselves the promise and hope of the journey. I invite you to grow with me as we help each other learn to see the beauty, to be touched by the symphony of God’s splendor. Let’s explore together the path through the wilderness he has prepared for us. It’s called the Way of Love, and it leads us home.

You may recognize the name of this path. The Way of Love comes from the Bible. “The Way” was one of the earliest terms used to define Christian community (Cf., Acts 9:2). Before we were called ‘Christian,’ we were known as the people of ‘The Way.’ The phrase itself was historically rich, finding its meaning in the prophet Isaiah’s good news to Jews captive in Babylon that God was preparing a way in the wilderness (Isaiah 43:19 (NRSV):

I am about to do a new thing;

now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?

I will make a way in the wilderness

and rivers in the desert.

‘The Way’ was first and foremost a vector, that long-promised pathway through the wilderness, cutting across rugged terrain, leading a people long oppressed to their home in a far-off country. And, as such, it was not a new phenomenon. In the First Exodus, God delivered them from bondage while trekking a similar path. In the wilderness, God forged them into a people whose mission is to flourish in holy friendship with God and each other. God sustained them, and gave them all they needed to live in such a way that all of the world is drawn into the ongoing gift of God’s eternally creating, sustaining, and reconciling action upon the entire created order. This Second Exodus carried forward that mission. ’The Way’ was a vector, a God-constructed path through the wilderness, along which God would craft a people to practice Jesus-centered life so that their love would make God’s transforming love visible to all the world.

I don’t remember too many songs from my boyhood, but I remember fondly how we always sang at the annual church picnic, “They will know we are Christian by our love….” As a boy, something innate in me recognized the pithy truth that song expresses. As an adult, I’ve learned to think of love as that which propels us toward union with those people and things from which we are estranged, alienated, separated. In other words, love is that which drives us to be reconciled, in the sense of bringing back together that which God intended to be together. Now whenever I hear that song, I translate it in my head it this way: “They will know we are Christians by the way we are being reconciled.’

It’s punts on the poetry, but that translation captures well the essence of the second dimension of ’The Way’ which early Christians understood. ’The Way’ is first and foremost a vector along which God delivers us, but it is secondly a means through which God is delivering us by driving us to be reconciled with God and each other. Along the Way of Love, God reconciles us. “They will know we are Christians by our love” because when we trek along the Way of Love, we are being reconciled, and it is that commitment to being reconciled in the Way Jesus taught us that makes us visible as a people. That’s why ‘the Way of Love’ also refers to a set of practices that shape the way we experience and respond to the world.

As I reflect now on the practices that Jesus taught us, I remember how, long ago, we prepared those almost-men for that Canadian wilderness canoe expedition. We taught them a set of practices, and then we practiced the practices until they no longer had to think about them to excel at them. That reflexive muscle memory was crucial when they needed to react to huge boulders that seemed to leap at them as their canoe raced down rapids.

So, for example, we taught them and repeatedly practiced the J-stroke so they could keep their canoe on course and avoid hazards. And, many times during the months before our expedition, we had them practice setting up camp in the dark, starting cooking stoves in the rain, balancing heavy packs while hiking through mud, and protecting their rest from the assaults of black flies at night. Most importantly, we taught them to manage the inevitable conflict that rose up in their exhaustion.

We taught them essential practices, and we practiced those practices, so that by the time we were halfway through the wilderness, things seemed to slow down for them. The anxious voices in their heads quieted. They stopped flailing at the water with their paddles, and could see beyond themselves and keep their eyes on the horizon. They experienced the symphony of God, and were touched by its splendor. Strength poured into them as they rested. They arose, still almost-men, yet transformed.

In a similar way, Jesus taught us essential practices that, once they become reflexive, make the world slow down, quiet the anxious voices in our heads, and help us to see beyond ourselves to all the amazing blessings God pours out on His creation. When we practice these practices, we can with increasing confidence locate ourselves at the coordinates where we too will experience the symphony of God, be touched by its splendor, and be transformed by the renewing of our minds. For Jesus taught us that when we do these things, He will be present.

And that’s the whole point of The Way of Love. That’s my invitation. To join me as we think about and practice habits of faith that prepare our hearts for the Spirit’s work of transforming us by the renewing of our minds (Rom 12:2). To that end, we’ll structure our dialogue around seven Jesus-centered practices emphasized by Presiding Bishop Michael Curry of The Episcopal Church: Turn. Learn. Pray. Worship. Bless. Go. Rest. Centered on Jesus, these habits are countercultural, and, when practiced, make us recognizable as Christians. More importantly, they train our hearts and minds to recognize and be alert for the gentle pressure of Jesus’ Spirit, guiding and delivering us through the wilderness to the place that is our true home.

Welcome to The Way of Love!